Special Session of Parliament: State of The Parliament as of Today

Asia News Agency

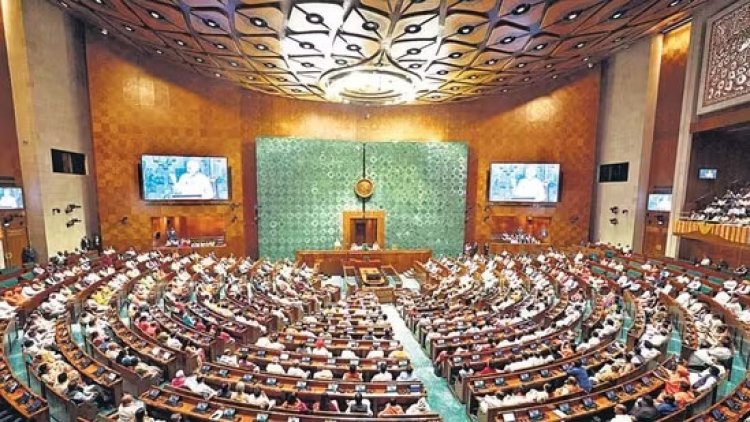

The much anticipated special session of Parliament began last week on 18 September. There was intense speculation about its purpose when the government announced the session dates that differed from the general parliamentary calendar. But there was some clarity about the next five days. The session was reserved exclusively for lawmaking and will not have any Question Hour. The government planned to get Parliament’s approval on five bills.

But that is not all. Farewell to the old circular Parliament building was also scheduled in this session. To commemorate the occasion, members of Parliament (MPs) reflected on the 75-year journey of our Parliament and deliberate on its ‘Achievements, Experiences, Memories and Learnings’. It is a critical conversation, writes Chakshu Roy (Head of Outreach at PRS Legislative Research) “that will help identify institutional changes required to strengthen the institution for the future. Legislatures, at their core, are forums for debate. They are the ‘grand inquest of the nation’ who, through discussion, shape our country’s future.”

‘House journey of 75 yrs’

It is therefore appropriate to reflect on the state of the parliament as of today. Harikrishan Sharma (Senior Assistant Editor • The Indian Express) sums up aptly the state: “Fewer younger MPs than in the early years of Parliament, more women voters but only a partial increase in women representation in the House, fewer sittings and fewer Bills, but an increase in the number of ordinances passed.”

He explains how the Lok Sabha looks like today.

Average age of members: As per Census 2011, about 66% of India’s population was below 35 years of age. Given the dwindling number of young MPs, the average age in the Lok Sabha has risen over the years — from 46.5 years in the First Lok Sabha (1952-57) to 55 years in the 17th (2019-2023).

Women MPs: Women’s turnout has been steadily increasing since 1962. Today, the figure of 78 elected in the 2019 Lok Sabha is the highest ever, but it is still only 14.36% of the total. That makes it less than half of the 33% seats envisioned to be kept aside for women by the women’s reservation Bill.

LS sittings: The maximum number of days the Lok Sabha met in a year was in 1956, when it held 151 sittings; while its lowest was in Covid year 2020, when it met for 33 days. The Rajya Sabha also saw its lowest number of sittings (33days) in 2020, and the highest (113 days) in 1956.

Bills passed:l Not only are both Houses seeing fewer sittings, they are also passing fewer Bills. The highest number of Bills were cleared by the two houses in 1976 (during the Emergency), when 118 Bills were passed. The lowest was in2004 (when the UPA-I government came to power), when the number stood at only 18. The second-lowest figure was in 2022, when 25 Bills were passed.

Rising Ordinances: With the Houses sitting for fewer days and passing fewer Bills, there has been an uptick in the ordinances promulgated by the Union government. From 1952 to 1965 (a period of stable Congress governments in power), the number was in single digits. From 1966 to the early 1980s (when the period of political uncertainty at the Centre began), it rose to double digits per year. Since 2013 (one year before the Modi government came to power), there has again been an uptick in the number of ordinances issued by the Centre.

Voter numbers: The electorate numbers have increased six-fold — from 173.2million in 1951 to 912 million in 2019. The Election Commission usually sets up a polling station per 1,200 electors in rural areas and 1,400 electors in urban areas. With the increase in the number of electors, polling station numbers have increased from 1.96 lakh in 1951 to 10.37 lakh in 2019.

More parties, contestants: The number of parties contesting Lok Sabha polls is 12 times what it stood in the first elections. Only 53 parties across India took part in the 1951 polls, while 673 did so in 2019. Like the number of parties, the number of contestants is also on the rise — from 1,874 in 1951 to 8,054 in 2019.

Since 2004, party in power has got highest votes: Of the 17 Lok Sabha elections held in the country so far, 10 have yielded a clear majority, while 7 have resulted in fractured mandates (1989, 1991, 1996, 1998, 1999, 2004 & 2009). During the periods of fractured mandate, there were occasions when the party with the highest number of seats received a lower percentage of votes than the runner-up. For instance, the BJP won the highest number of seats (161) in 1996, but its vote share (20.29%) was lower than that of the Congress (28.8%) — which came runner-up with 140 seats. A similar trend was seen in 1999 and 2004. But since 2004 (when the UPA I government first came to power), this trend has reversed, with the winning party receiving a higher vote share than the runner-up.

Less time on questions: The time spent by the House on questions has seen a decline. While the First Lok Sabha (1952-57) spent 15% — 551 hours and 51 minutes of its total time of 3,783 hours and 54minutes — on questions and answers, the figure fell to 11.42% during the 14th Lok Sabha (2004-2009).

Disruptions

Shashi Tharoor (third-term Lok Sabha MP for Thiruvananthapuram, representing the Congress party, and is the longest-serving Member of Parliament in the history of that constituency) mentions some other practices that need to be looked at.

The present times have seem disruptions of the two houses frequently. This practice, writes Shashi Tharoor (third-term Lok Sabha MP for Thiruvananthapuram, representing the Congress party, and is the longest-serving Member of Parliament in the history of that constituency) “sadly, is often par for the course in India’s Parliament, many of whose members (and not only in the Opposition) appear to believe that the best way to show the strength of their feelings is to disrupt the lawmaking rather than debate the law. Last session, the Opposition parties united to stall both Houses almost every single day. While that was extreme, there has not been a single session in recent years in which at least some days were not lost to deliberate disruption.”

Code of conduct for MPs repeatedly breached

In the seven-and-a-half decades of Independence, some British practices have “faded and India’s natural boisterousness has reasserted itself. Some of the State Assemblies have already witnessed scenes of furniture overthrown, microphones ripped out and slippers flung by unruly legislators, not to mention fisticuffs and garments torn in scuffles among politicians. While things have not yet come to such a pass in the national legislature, the code of conduct that is imparted to all newly-elected MPs is routinely breached.” But even in the national legislator, “standards of behaviour prevail that would not be tolerated in most other parliamentary systems.”